It’s like Tetris.

Finding product-market fit seems easy until you realize it’s too late and the horizontal block should have actually been vertical all along.

How can you organize the pieces of the product-market puzzle to fit together perfectly? In hindsight, it appears the companies that successfully achieve product-market fit do so with a detailed map from the start, but this is usually not the case.

In this article, we explain what product-market fit is, the various states of it, and processes to help you achieve it. Continue reading or jump to our full infographic below.

What is Product-Market Fit?

Product-market fit is the intersection of the supply of product and demand from customers.

Let’s look at the street view of this intersection.

When we say the supply of a product we mean any allocation of resources, whether that be human capital, computational servers, or physical inventory.

But a product is only as great as the market it serves. This is why demand from customers is the secret sauce.

It’s possible that the market a product was originally built to serve transitions, or more commonly, the product is improved to better serve that market. Either way, product-market fit is a process, not a panacea.

To determine if a product-market fit exists, it’s important to take an iterative and analytical approach to product management and development. The first step is building a minimum viable product-market fit (MVPMF).

Minimum Viable Product-Market Fit

Are you building for billions?

Most people would place companies like Apple and Facebook on a pedestal and assume they were built for billions from day one. But let’s not forget how they found product-market fit.

The first Apple computers on the market were hand-made boards built for hobbyists. Facebook was originally available exclusively for Harvard University students.

These are indisputably niche markets but today you are in all probability a user of products from Apple, Facebook, or both.

These companies were not originally built for the general public and instead got their start with a much smaller market of early adopters. It wasn’t until much later that these companies crossed the chasm to serve the general population.1

Implement this strategy in your business by starting small and learning from all. Addressing the needs of a small group of early adopters allows your team to learn what they want and build the tools that the general population will feel comfortable using.

Product-Market Pivot: Fitting the Product with the Market

Did you do your customer discovery interviews?

You may have taken this advice from nearly every startup advisor ever and received an overwhelmingly positive reception during your customer interviews.

But then you built it and… they didn’t come.

You can push all you want to build customers the baseball diamond from Field of Dreams, but if they actually want to play football, then no one will use your product.

Enter the product-market pivot.

And we’re not talking about multi-purpose fields.

A leading indicator of true product-market fit is customer pull, not your push. We’re not saying that you will never have to do marketing again if you achieve a fit. We’re saying that customers should be asking you for more products and features — you shouldn’t have to ask customers to use them.

Product-Market Pivot Example

In 2007, Justin.tv launched as a 24/7 reality show about Justin Kan. Justin and his business partner, Emmett Shear, were validated by a $50k investment from Paul Graham of Y Combinator and a significant amount of media coverage.

Turns out, the market didn’t really care about Justin Kan’s every moment and would rather broadcast their own live streams. After a pivot to user live streaming and the subsequent product-market fit, Twitch was born and later acquired by Amazon for just shy of a billion dollars.2

Sometimes, as this story reveals, the market will tell you what they really want, and other times they’ll mislead you. It’s important you rely on usage metrics in addition to customer feedback. Never rely on customer feedback alone.

Does the Market Recommend the Product?

More often than not, customers are talking about you behind your back.

The question is, are they singing your praises or talking smack?

Many people advocate for measuring a Net Promoter Score (NPS) which is the result of asking users the likelihood they would recommend your company to a friend using a zero to ten scale.

Unfortunately, the NPS can be a vanity metric. NPS is just another instance of relying on what users say, not what they actually do. The question remains unanswered: are customers actually recommending your product?

Tracking referral and conversion rates, formally known as the viral coefficient, gives real insight into whether customers are advocating on your behalf or recommending otherwise.

Many companies try to incentivize customers to refer their personal networks. Unfortunately for many, this strategy only works when the product is worthy enough in the minds of users to share.

The mutually beneficial referral program implemented by Uber and Robinhood, for example, works well for them because their product is easy to use and relevant to most people.

How to Find Product-Market Fit

It’s like the Enigma machine, only harder to crack.

Ok, maybe not that hard.

If you are attempting to crack the code of product-market fit, it’s most important you remain agile and open-minded.

Agile in the sense that you will need to be ready to pivot when the market passes judgment with their purchases or lack thereof. Open-minded in the sense that sometimes it takes time for your product to percolate in the minds of market makers.

Steve Jobs gave insight into his perspective when he said:

“Some people say, ‘Give the customers what they want.’ But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, ‘A faster horse!’”

Jobs summarized his methodology when he said: “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”3

Thinking of product-market fit as a puzzle seems like a great analogy. You try to put the puzzle pieces together and when they don’t fit, you reorient them to test a new approach until you find the right fit.

When beginning a new puzzle, it can be easiest to start with the edges because they have one flat side. When launching a new product, this edge case strategy can mean easing the product into the customer’s life by anchoring it to an existing idea.

Unfortunately, the puzzle, in this case, would have pieces that morph their shape while you are attempting to piece them together.

Let’s use Uber as an example of this. Uber was able to find product-market fit by anchoring their product to the existing luxury black car service industry. Once they proved the product fit within the smaller market for high-end black car services, they were able to enter the larger market as an alternative to taxi services.

Time To Product-Market Fit (TTPMF)

The notion of TTPMF was first proposed by Andrew Chen in his article, Minimize your Time to Product/Market Fit.4

So how long can you expect market fit to take?

Unfortunately, it can take decades or even longer to culminate. Some of the recent unicorn companies to come out of Silicon Valley were actually products that previously failed to find product-market fit many years ago.

Let’s consider grocery delivery as an example. Today, companies like Instacart, Shipt, and others are successfully servicing a market for grocery delivery. But this is not the first time this product has been tried. In 1996, Webvan was launched as an online grocery business but by 2001, had become one of the largest failures of the dot-com era.

The market wasn’t ready for grocery delivery in the late ‘90s but is more receptive today.

Other products find their market fit like a flash in the pan, only to smoke and burn out shortly thereafter.

So how do you achieve it more rapidly?

Steps to Product-Market Fit

There’s no easy street on the way to a fit, but there are detours that can save you from encountering a roadblock and forcing you back to point A.

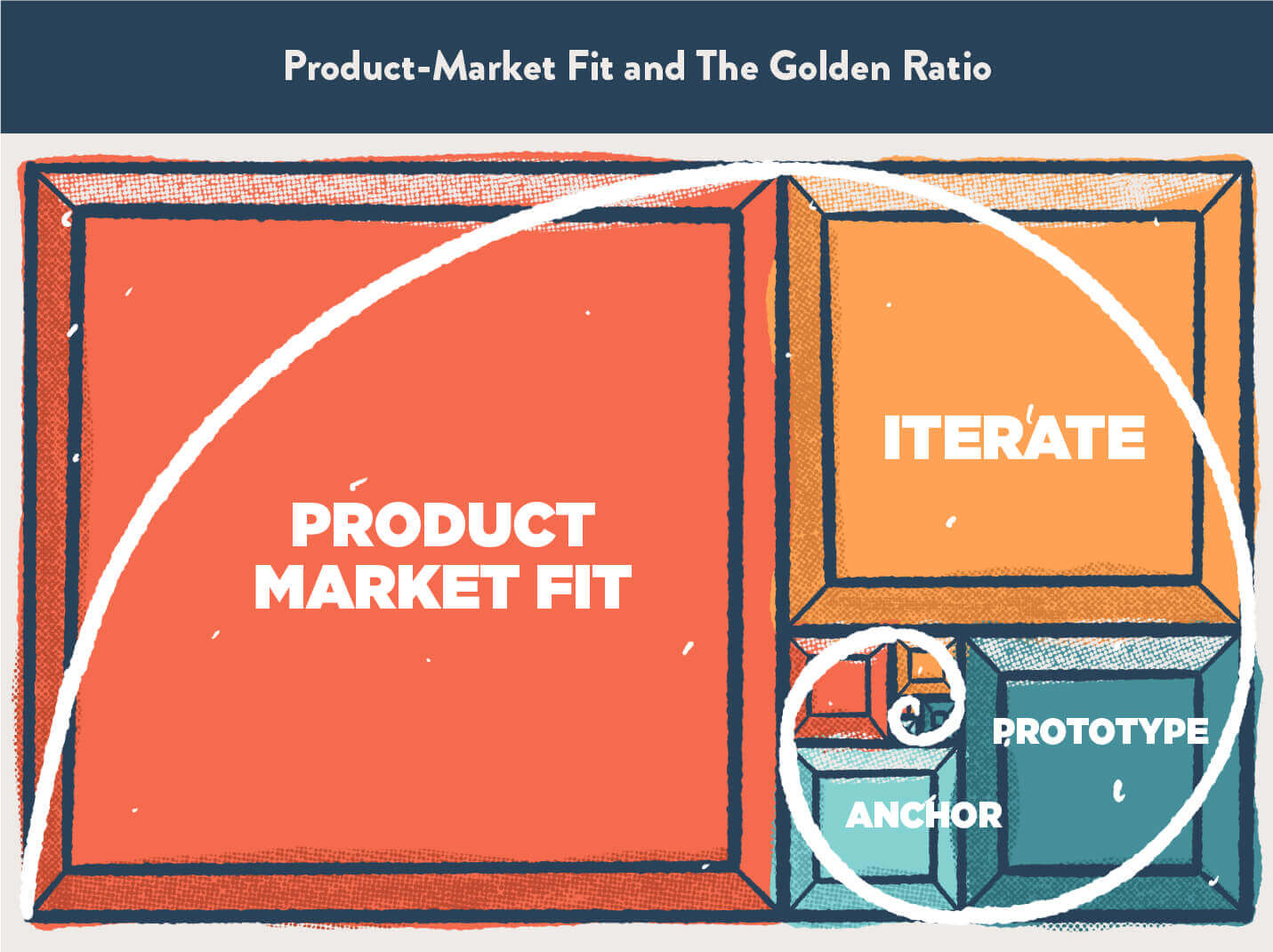

In nature, the mathematical phenomenon of the Fibonacci sequence is present in the formation of shells, hurricanes, and galaxies. The steps to achieving product-market fit can also be visualized as the golden spiral.

The golden ratio expands out to form the golden spiral. From the epicenter outward the spiral gets wider with each quarter turn by a factor of phi (the mathematical constant). When finding product-market fit the progress seems to follow a very similar pattern until finally achieved.

Anchor

We’ve already covered this idea above, so we’ll keep it brief. Many people say, “Don’t reinvent the wheel.” But let’s amend this to:

Don’t reinvent the wheel; instead, reimagine how the wheel can and should be used.

Prototype

One of the most effective strategies for quickly determining product-market fit is to prototype. By building a prototype and testing on a small scale, you’re able to limit your investment and exposure.

Testing the same prototype within multiple industries could reveal an opportunity for your product to do well within an unforeseen market.

Keep in mind that no prototype has ever survived the first contact with customers and remained unchanged. Prototypes are meant to be broken and improved upon. The next strategy is a continuation of this thought process: iteration.

Iterate

Navigating towards product-market fit requires an iterative approach. In reality, iteration will likely dominate the lifecycle of any business because, without evolution, the natural selection of business models will render many extinct.

Consider for a moment if companies like Apple and Amazon had never iterated their products and business models. Apple would still be selling computer kits to hobbyists and Amazon would be a mere online book store.

Learn from your prototyping and continue to implement your observations and customer feedback.

Don’t forget that markets can evolve as much as products do. If the dynamics of your market begin to shift, you may need to redefine your product-market fit.

Product-Market Fit: More Game Theory Than Puzzle

Is a puzzle actually a good analogy?

The product-market fit puzzle is actually more akin to game theory. In game theory, you strategize to navigate competitive situations in which the action depends on the actions of others.

Product-market fit is not like a Rubik’s Cube puzzle, for example, that has a repeatable algorithmic solution. The game solution changes with each player’s move. This is why you should approach it as a chess grandmaster would: have a plan but also the willingness to change that plan if an unexpected move is made.

Maybe one of the most appropriate quotes for planning market fit is from former heavyweight boxing legend Mike Tyson: “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

If you are navigating product-market fit and want to learn more about your customer, download our guide about how user intent is redefining customer engagement.

The Intent Based Segmentation Guide

Subharun Mukherjee

Heads Cross-Functional Marketing.Expert in SaaS Product Marketing, CX & GTM strategies.

Free Customer Engagement Guides

Join our newsletter for actionable tips and proven strategies to grow your business and engage your customers.